DAVID RIFF barely survived the Moscow Biennial and asked himself whether there is such a thing as aesthetic conservatism in the good sense of the word

Right after the opening of the Moscow Biennial, I came down with a terrible flu. While my fever was high, I had violent dreams of the main project's one-way-street of bird cages, wellness rooms, and security guards. The word "neoconservatism" kept passing through my mind. The sicker I got, the more it bothered me. No matter where you turn, you hear new myths about the nation and the artist, new stories about the "magic" quality of art, its "auratism" and its "exoticism." Whoever speaks in this way thinks he or she is resisting the glamorous esperanto of the global mainstream with a particularly intelligent strategy, when actually, this strategy itself is quickly becoming the mainstream.Neo-conservatism has gone pandemic in Moscow, leading to catastrophic results, which you could see quite clearly at "One Sixth of the World Plus. Second Dialogue," curated by Konstantin Bokhorov at Zurab Tseriteli's Gallery up on the Prechistenka. One of Anatoly Osmolovsky's totems much like the one at the biennial's main project at the Garage. Bokhorov investigates what he sees as the neo-conservatism of art from post-Soviet space over the last decade, which he defines as an actualization of modernist strategies with a strong national and local color. To get to his exhibition, you have to go through the space of sculptor Zurab Tsereteli's personal museum with its huge symbolic apple and Putin in a faux Boccioni judo wrestler's pose. So throughout, you can't help but wonder. When post-Soviet pseudo-traditionalist neo-modernisms meet real homegrown conservative kitsch, is one really so different from the other? Somehow, my feverish mind kept revolving around this question, a stalled dialectic collapsing into formless negativity.

But as I started getting better, I started asking myself if one could imagine a situation in which this dialectic did not collapse. Is there such a thing as aesthetic conservatism in the good sense of the word? And what would it be today? How do you formulate it as a practice in the face of a deluge of neo-conservative strategies? Of all the exhibitions I saw during the Moscow Biennial, only two really stuck in my mind in this connection. One was a show of new metalworks by Dmitry Gutov, the other a solo exhibition of new photos and videos by Olga Chernysheva.

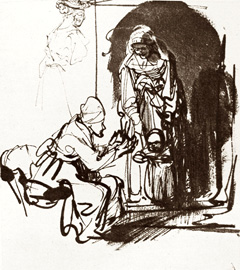

Dmitry Gutov. From the cycle "Rembrandt's Drawings." Woman Teaching an Infant to Walk. Side view. 2009

Gutov's new work was appropriate to this setting. There was a pianist playing Beethoven at the vernissage. Approaching from afar, you could see canvas-size metalwork reliefs, hung with wires from the ceiling. These "fences" (they refer to the forms that arise organically in fences marking illegal enclosures in Kuzminki Park, as Gutov explains in the exhibition catalogue) are much more elaborate and have more depth than those shown at documenta 12; they look like unruly modernist sculpture, dangerously close to some alternative half-official Soviet salon. Detailed cross hatchings, fine-grained sensuality, virtuosic welding with daring curves and marked seams; haptic pleasure on the verge of disgust, intensified by a pervading sense of how outmoded the formal repertoire of the early 20th century really seems today. Precisely the kind of art that would have provoked the wrath of Mikhail Lifshitz, Gutov's favorite thinker. "There is so much violence in all this expression," I heard somebody say.

But then, click, you find the right position and it all makes sense, that particular point in the room from where all that modernist shit turns into a faithful translation of pure aesthetic gold, which, as every conservative knows, is Rembrandt, not just Rembrandt the painter, but of course, even more, Rembrandt the draughtsman, whose prints have been reproduced for the petit bourgeoisie since time immemorial. (Gutov, too, has added to this collection of reproductions: the exhibition is accompanied by a pocket volume juxtaposing his own work with Rembrandt's, available for a "democratic" price at Falanster Bookstore.)

These metalworks are three dimensional blow-ups of those familiar reproductions; they repeat every penstroke naturalistically, after leading the "hungry" spectator through a garden of follies and illusions (much like the gardens we see at the Moscow Biennial's main project, or in the past, at the Venice Biennials or documenta 12). There is something violent in the naturalism that breaks through all the layers of potential kitsch. After "recognizing" or "gathering" the illusion, you can't go back to appreciating all this expressive scrap metal, however virtuosically it has been bent. After the Rembrandt metalwork went "click," all I could think about were fences, enclosures, and the illusory freedoms of the contemplative private life, whose abstractions and follies seem so threatening precisely because they are not illusory but real. Gutov demonstrates two aesthetic conservativisms, one modernist, the other "classical;" he shows how much danger and conflict is in their dialectic, and how this dialectic can ultimately collapse, though not into formless negativity, but into a new form, experienced at first as an amusement, then as a dead object, and then, finally, most fruitfully, as a real image, an image used for thinking.

The other show that stuck in my mind was Olga Chernysheva's "Past Present" at the Red October Chocolate Factory, a show that almost folded under the pressures of the extremely competetive parallel program, where everyone and their brother felt the need to represent a grand new masterpiece. Originally planned for the ruin in the Museum of Architecture, it was relocated in the last moment and given a very difficult space by Baibakova Projects. Chernysheva's exhibition dealt with that challenge masterfully, presenting two new photo-series and two new videos in a perfectly dosed, extremely coherent exhibition.

What seemed so interesting to me was that it could be read as an immanent critique of the Third Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, even though it was almost certainly not intended at such. As Boris Groys puts it in his text for the exhibition, Chernysheva does not exhaust herself in a search for the right new strategy, bringing "art to life;" instead, she finds "art in life," and this art, as Groys puts it, is inevitably a critical gesture. Precisely that method, to me, would be conservativism in a good sense of the word.

Take for example, Chernysheva's black and white photo prints, which feature the security guards that we all know from the Garage. I don't think Chernysheva wanted to demask anyone; she simply lives around the corner. The security guards are simply part of a familiar reality. Perhaps it is this familiarity that allows her security guards to pose as "guardian angels." Sharp camera angles and almost-mannerist poses make it seem as if they could lift off or fall at any moment; only their shadows bind them to the walls. One of them has the city of Moscow as his halo, and really, about 30 percent of the city's male population is working as security guards, a reserve army of labor, whose chief activity, in the absence of outright class war, is to wait around and to demonstrate the latent violence behind the unquestionable order of things. What Chernysheva does is to reveal the everydayness and the uncanny singularity of these minders on duty, who never quite correspond to their job; she treats them conservatively, caringly, without resorting to the grotesque that this topic would usually provoke, allowing her characters - typical people under typical circumstances - enough leeway to demonstrate their own singularity. But in doing so, she only makes matters worse, showing how all that latent violence shapes its own "authentic" forms of subjectivity and transcendence under conditions of total heartlessness, conditions that, by now, are considered totally normal.

I immediately read Chernysheva's lightbox series of a cactus seller in the entrance hall of Moscow's zoological museum in a similar key, as an oblique comment on the aesthetic of the main project at the Garage. Because actually, Jean Hubert Martin tries to draw upon a sense of wonder that comes from antiquities shops, ethnographic displays, and, perhaps most importantly, natural history museums. But Chernysheva is not simply sending us to the original place whose wonder that the magic-show in the Garage cannot reach. Instead, she investigates the conditions under which this "magic" of dead nature emerges. The story, told in the commodity-conscious form of the lightbox, begins with the cactus seller who hoards over his glass case in the lobby of the natural history museum. The collection of prickly forms it contains is much like Chernysheva's fur and wool hats, rounded yet prickly and resistant. The cactus seller is an obsessive collector; each cactus is classified according to age and genus, and thus given a value, not only as private property but as an instance of some divine order to which the cactus seller can provide access in grumpy explanations. The forms add up to a personal garden whose strange "magic" then spreads out over the entire animal kingdom of skeletons, hermit crabs, and stingrays.

It would be best to stop there, and to let Chernysheva's "good conservatism" settle for a bit. The problem is that Chernysheva's photo series were flanked by two videos in which she examines the role of the artist in such a reality. Both videos are about how structures of everyday violence are internalized and lived, and how they eventually turn into a strange form of contemplation in which alienation becomes a mixture of distance and total absorption. One sees this, for example, in one of the new videos, a 18mm reenactment of a Pavel Fedotov painting with the tautological title of "Encore, again, Encore" (1852): a comfortable looking young man lies bellydown on a sofa and makes a poodle jump over the same stick again and again. What we see here is the sparse interior of the new Russian Biedermeier, that everyday laced with coercion, violence, and festering political potentialities. An old b/w/ television on a table shows static in the carefully composed interior, replacing Fedotov's snowy window. It reminds me not only of that catastrophic moment when broadcasting and internet break down temporarily, but also of the blinding snowstorms like the one during the first Moscow biennial. Repetition anticipates the industrial drill: the dog is the artist who has to keep doing the same trick. But at the same time, the trainer is meditating, engaged in a labor of love verging on pure contemplation. He is absorbed with the dog's slow progress toward perfection, and, like Chernysheva, he remains unmoved by all the glamor that we could see if the television were on.

- 29.06Московская биеннале молодого искусства откроется 11 июля

- 28.06«Райские врата» Гиберти вновь откроются взору публики

- 27.06Гостем «Архстояния» будет Дзюнья Исигами

- 26.06Берлинской биеннале управляет ассамблея

- 25.06Объявлен шорт-лист Future Generation Art Prize

Самое читаемое

- 1. «Кармен» Дэвида Паунтни и Юрия Темирканова 3451965

- 2. Открылся фестиваль «2-in-1» 2343488

- 3. Норильск. Май 1269064

- 4. Самый влиятельный интеллектуал России 897784

- 5. Закоротило 822278

- 6. Не может прожить без ирисок 783176

- 7. Топ-5: фильмы для взрослых 760040

- 8. Коблы и малолетки 741281

- 9. Затворник. Но пятипалый 472185

- 10. ЖП и крепостное право 408062

- 11. Патрисия Томпсон: «Чтобы Маяковский не уехал к нам с мамой в Америку, Лиля подстроила ему встречу с Татьяной Яковлевой» 403536

- 12. «Рок-клуб твой неправильно живет» 370846