DAVID RIFF comes close to collapse as he visits the first portion of exhibitions at the Moscow biennial's parallel program.

Last night, I went to the first openings of the Moscow Biennial's parallel program, and I have to say, I am already horrified. Not at the art, which was not all bad. In part, it's the marathon ahead. As we know there are about 60 events. And this is way too much. It looks like a reverse image of burning corn in the Great Depression: combat the Great Recession by supersizing the art biennial. Cut back on the discourse. Exhibit art by the ton. "It's always like this," people were saying to me last night, as I moved from the opening of Boris Mikhailov and Vladimir Tarosov via Art Play on the Yauza to Winzavod. But I have to tell you, it's not. The Third Moscow Biennial is distinct from the First and the Second. And if the central project has taken on an nearly museal stature, the parallel project is now bloated beyond belief and has taken on a life of its own.Supersize it: you wouldn't know it from the press releases, but Boris Mikhailov actually has a partial retrospective at the Manege, organized by the MDF and curated by Olga Sviblova. Strict, almost academic hangings of older work make the best of a problematical space (Mikhailov himself says it's a "Soviet salon"). The show gives a complete overview of his central themes: the explosive ambivalences of the Soviet way of life that eventually die down and sink back into the Lumpenized dusk of post-communist stichii. The problem is that it would take at least two hours to really fathom the extent of Mikhailov's epoch-making scope, part of which you can see here. Two hours that you don't have if you're rushing from one part of the parallel program to another. So, as a gesture, it seems misplaced, overkill, as we say in English. This has no bearing on the work itself (which is brilliant and anyone should see), but on its mediation to an audience that is already strained. Good thing the opening was the first of the evening for me, and not somewhere in the middle of this whole event totality (sobitinaya total'nost).

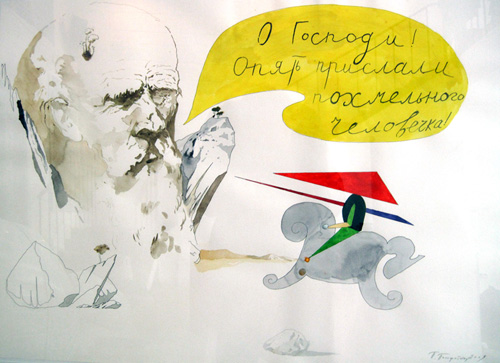

"REALLY?," the exhibition of Russian "post-post-modernists" at Art Play at Yauza seemed similarly misplaced to me (boleet tem zhe), but in a different way. Here, the biennial is a good occassion to upgrade a recently vacated industrial shopfloor in the Manometer factory with a temporary use. The show continues themes taken up in the summer with shows like "Natasha and the Machine" or "Occupied City," and includes many of the same artists, although there is no overt curatorial ideology. The lacadaisical scepticism of the question "Really?" is a little too cyncical to sound like understatement, so that the work itself has to fight hard not to look like just another collection of objects, wall-hangings, and videos. The intended minimal poetics never quite take shape, maybe because the show is slightly overloaded, with appropriately gritty work by "old masters" like Gutov, Osmolovsky, Korina, Alimpiev and Kulik interspersed for effect, but no apparent curatorial effort to deal with the complicated dialectic between the generations. What holds the show together is a sense of vague political potentiality gone sour in reductions to minimal form (this is the central problem of modernism that repeats in endless chains of the prefix post). This potentiality that would have long since evaporated, if it weren't underwritten by the space itself (industrial space is always vaguely political because it was once inhabited by the protelariat, and now becomes a production site for the "off-scene" before it is fully gentrified), and by the efforts of the young artists, whose unresolved search for meaning can only be applauded.

I got stuck arguing with my comrades at Art Play, so I came late to Winzavod, where the openings of Joep Van Lieshout's "Slave City" and Regina's showing of new work by Sergei Bratkov were already closed. (It would be interesting what people thought about Lieshout, and if you have an opinion, please do leave it in the comments; to me, the work is intriguing as a science fiction cabinet of horrors, but I think it's a little too flat formally, and I can't quite put my finger on why. But as a curatorial gesture, Lieshout's presence seems very well-placed, presenting the kind of show one would expect of a non-profit parallel program for a biennial, and one that clearly comments the price of inclusion, the main project's central theme. Watch the interview with Joep van Lieshout on OPENSPACE.RU, and you will see what I mean.)

I only saw two shows last night at Winzavod. One of them was a gallery show of commercial neo-modernism and glamorous photography by the gallery Art and Art that I won't discuss at length, another was "Fuck Young," curated by Vladimir Ovchinikov's 19-year old son, who has a very clear curatorial position regarding his own generation: fuck them all. The alternative? The older generation of the 1990s, the backbone of commercially successful, baudy Russian art on the edge to travesty and ethnokitsch. Which is not always bad, to be sure: on the top floor of the space, there is a hilarious piece by Sergei Bratkov, who mimes Ukrainian folk figures with a comedic talent that had me close to pissing my pants with laughter. But on the whole, there was something brash and as of yet unreflected about the way the show structured its selection of commodities. This is fine, I guess, because it is the work of an art dealer's son, using the platform of a biennial parallel program to learn the business. But that pose contains no small dose of exhibitionist class-arrogance, too, if one looks more closely, and that, I would say, reflects the spirit of the Third Moscow Biennial on the whole. How else can we explain such an incredible hunger for self-representation?

- 29.06Московская биеннале молодого искусства откроется 11 июля

- 28.06«Райские врата» Гиберти вновь откроются взору публики

- 27.06Гостем «Архстояния» будет Дзюнья Исигами

- 26.06Берлинской биеннале управляет ассамблея

- 25.06Объявлен шорт-лист Future Generation Art Prize

Самое читаемое

- 1. «Кармен» Дэвида Паунтни и Юрия Темирканова 3451972

- 2. Открылся фестиваль «2-in-1» 2343491

- 3. Норильск. Май 1269071

- 4. Самый влиятельный интеллектуал России 897785

- 5. Закоротило 822287

- 6. Не может прожить без ирисок 783195

- 7. Топ-5: фильмы для взрослых 760070

- 8. Коблы и малолетки 741296

- 9. Затворник. Но пятипалый 472194

- 10. ЖП и крепостное право 408062

- 11. Патрисия Томпсон: «Чтобы Маяковский не уехал к нам с мамой в Америку, Лиля подстроила ему встречу с Татьяной Яковлевой» 403540

- 12. «Рок-клуб твой неправильно живет» 370855