Igor Makarevich and Elena Elagina enter into a dialogue with Brueghel and Duerer

Walk unsuspecting into the west wing of the Kunsthistoriches Museum’s picture gallery and you could be forgiven for thinking you’d eaten one of the magic mushrooms Igor Makarevich and Elena Elagina have long made their own. The hall with ten paintings by Brueghel, arguably the museum’s crown jewels even among the Reubens, Titians, and Carravagios and undoubtedly the best collection of the Belgian’s works in the world, is now taken up by an updated version of the Conceptualist duo’s Mushroom Tower (2003-9). That is the centerpiece of In Situ, an exhibition curated by Professor Boris Manner of the Vienna University of Applied Arts and organized by Stella Art Foundation, featuring around 50 works from various series over the last 30 years side by side with masterpieces printed in every first-year art history textbook.The exhibition seems a rather odd choice for a museum that one wouldn’t normally think of associating with contemporary art. With the MuseumsQuartier that is home to Vienna's Kunsthalle and MUMOK, its contemporary art museum, just a walk across the street, not to mention the KHM's grandiose imperial surroundings and world-class collection, it's difficult to see why they would see the need. But they are certainly moving in that direction. In 2004 the museum organized a Francis Bacon retrospective, while in October it began its collaboration with the Stella Art Foundation with "That Difficult Object of Art", mainly consisting of SotsArt and Moscow Conceptualist works from the foundation's collection.

It was the Bacon, however, that served as prototype. Under the title “Francis Bacon and the Tradition of Art”, it explained Bacon’s obsession with various old masters by placing his works side by side with their source material. His Oedipus and the Sphinx (1983) was joined by the Ingres “original”; others were matched with the old masters whose technique they had cribbed, be they Titian’s “veils and striations” or Picasso’s distortions. And the Velazquez Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650) that famously “haunted” Bacon was placed alongside some of the “screaming popes” its reproduction in books inspired — and in an ironic twist, the Galleria Doria Pamphilij in Rome that owns it refused to lend it to the KHM, forcing them to borrow a copy.

Manner’s curating, however, makes even this look a little base. It is not so much an art history lesson as an attempt to place the classical in dialogue with the contemporary, and thus shedding new light on both. So if the previous Russian exhibition could be interpreted as an attempt to make strides into contemporary art per se, with the works all shown on their own, this one seeks to actualize not just the museum, but the works themselves. This is not so much to say that Brueghel and co benefit from their association with Makarevich and Elagina in the way they do from them — in the PR sense, at least — but that by the sheer virtue of their relative newness they have the ability to brush up the dusty old masters generations of Viennese children are presumably dragged to see as children and do not understand.

In that way, then, it is an effort to present both the classical and contemporary works entirely out of their context and approach them in a way impossible were they on their own. With artists like Makarevich and Elagina — and Russian artists of the period in general — this is a necessity if the Western viewer, with no knowledge whatsoever of the context, is to get anywhere near understanding their work.

So instead of attempting to place Makarevich and Elagina within their own context, Manner instead puts them in the context of classical art. The most obvious connection is the Mushroom Tower, a Roman column supporting a small model of Tatlin's tower on a toadstool base, with Brueghel's Tower of Babel (1563). As Makarevich explained, this painting had played a crucial role in his artistic development and much of what came after. "When I was young, I came across a reproduction of Brueghel's 'Tower of Babel' in a textbook," he said. "It set me a riddle. All my life, I tried to solve this riddle, and I felt I never did. You could call a large number of the works here attempts to answer it. This tower was always on my mind. It reminded me that Elena and I were born in a great utopia, although we found it at the ppoint of total disintegration. We were little bricks in some huge, imcomprehensible building."

Here Makarevich and Elagina intelligently highlight the significance of Brueghel's Tower. The obvious point of it, as with many of his works, is his resetting the Biblical scene in the Flanders of his time, giving it a then-contemporary resonance and emphasizing its relevance by renewing the scene — its resemblance to the Roman Colosseum touches a keenly felt medieval Christian nerve of oppression. Makarevich and Elagina’s tower obviously does the same, with Tatlin’s never-built Monument to the Third International representing the unrealizable utopias of the Soviet Union, the Roman column their historical precedents (at once including Brueghel), and the mushrooms themselves the collective hallucinosis brought on for shamans with toadstools and for homo soveticus by revolutionary delirium.

What the juxtaposition does is emphasize the strictly human element at the heart of both works. Breugel's Bablyonians are doomed to failure not because of a divinely ordained confusion of tongues, as in the Bible, but because of technical difficulties. They are seen hard at work on the tower's upper reaches without having finished its foundations; the arches are built perpendicularly to the ground, though the tower appears to be made out of concentric pillars and is rising in a spiral; some of it is already collapsing, for which the king is already punishing some peasants in the foreground. Makarevich and Elagina's is, presumably, not intended as architectural criticism of Tatlin, but reminds us of the human cost that comes with attempts to realize any utopia; its original 2003 incarnation was held up not by a Roman column, but by Socialist Realist-stylized heroic working men.

In the next room two huge fish market scenes by Frans Snyders do not so much enter dialogue with Makarevich and Elagina's Closed Fish Exhibition (1990-8) as they become part of it. Their original work was itself an appropriation. Inspired by the discovery of a catalogue to a 1935 Socialist Realist exhibition organized by Volga-Caspian State Fishfarm in Astrakhan, from which only the titles remain, Makarevich and Elagina set out to “reconstruct” the paintings. The success of their result is due in no small part to their “faithfulness” (for lack of a better word) to the spirit of the originals. Where titles like Still-Life. Fish (1996) and On the Landing at Kuybyshev (1990) were originally meant to evoke the triumph of ideology in art, here they are disintegrated into mere words and things. In Makarevich and Elagina's hands, they become a riverside landscape painting in a classical frame and a wooden plank in the shape of a fish, both with pipes poking through their surface as if to drain the water from them.

Manner's interpretation of the titles is as of «[our guessork] as to what the lost originals might look like with the objects on display," making the Closed Fish Exhibition "capable of drawing quite complex conclusions as to the relationship between the signifier and the signified." Despite Snyders' works dwarfing theirs in size, with only four works from a very large series at that, it seems as if his fish markets have become part of Makarevich and Elagina's reconstruction. Here they come to represent the unrealizable ideal behind the commissioned exhibition, dwarfing the sketches and studies of the socialist realists. If Makarevich and Elagina's framed pseudo-paintings are manifestations of what the artists seem to have produced in 1935, Snyders' have become what the Volga-Caspian State Fishfarm hoped for in the catalog's word of welcome: that "having seen the work of the artists, the audience might help them to paint more canvases about fishing, cavases appropriate to the socialist fishing industry."

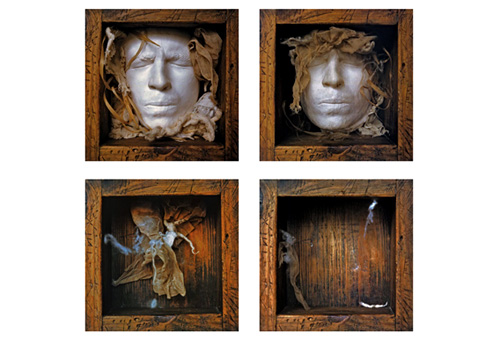

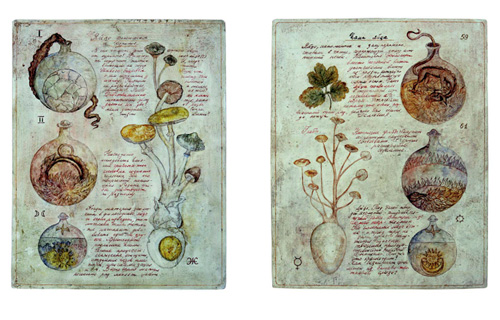

The works in the narrow corridors of the KHM’s picture gallery are placed there to comment on centuries-old artistic themes and thereby show their timelessness. Makarevich’s Change (1978), a series of photographs detailing the destruction of his gagged and framed face, lines one wall opposite works by Albrecht Durer. The latter was one of the first to develop the theme of the artist as subject, a theme whose certainty Makarevich questions and debases, making a multitude of himself to pose against the idea of the single “I” and thereby the notion of identifying the artist through personal stylistic idiosyncrasies. The Laboratory of Great Deeds (1995-2006) Elagina’s series dedicated to the Soviet pseudo-scientist Olga Lepeshinskaya, is placed in the context of medieval alchemy by presenting it as part of the museum's permanent exhibition. And it looks entirely authentic. In a way this is in itself a fantastic trick, blurring the lines between contemporary and classical as the alchemists sought to do between magic and science.

Manner's next step moves away from the classical as is and towards the classification of the contemporary. With no obvious parallels in the KHM's collection, Makarevich's Homo Lignum series (1996-2004), a study of an fictional Soviet factory worker who, alienated and depressed, tries to turn himself into a tree, is simply integrated into it. The idea here is to transform Makarevich by museifying him. And against all expectations, this too seems a natural move; Burattino and his Soviet surroundings will be foreign to the viewer, but no more foreign to the Biblical scenes and mythical monsters that surround them. The only work in the whole exhibition, in fact, which looks out of place is Makarevich's Ganymede (2004), a parody of a Rembrandt which appears not to have made it out of Dresden. Given the obvious link between the works — Makarevich has substituted Burattino, the Soviet Pinocchio — this is primarily due not to Makarevich's work, but to the printed reproduction of the Rembrandt, measuring up neither to the original nor to its reinterpretation.

As hallucinogenic as seeing these artists in such exalted company seems to the Russian, this must surely pale in comparison to what Austrians must feel at having their museum invaded by these strange bedfellows. There's little, however, to be gained from reading the local reviews. Many of them simply recycle the press release (which would never happen in Russia — our [sic] critics would have written it themselves, of course), and the rest seem almost lost for words. “Amongst motivic quotations, Kafkaesque spiked noses and absurd sculptures the gallery, and the building around it, become on the one hand an intrinsic part, on the other an immediate justification of the contemporary,” commented Kleine Zeitung; Die Presse’s Barbara Petsch was dumbstruck by the Mushroom Tower, writing, “The mushroom triggers visions reminiscent of inebriation and bordering on hallucination. He who ascends Makarevich’s Tower does so in his imagination.”

Vienna, after all, seems an unlikely place for such an experimental exhibition. It is a Catholic city with Catholic tastes; placid and calm in tempo, with cafes in the MuseumsQuartier populated by dour-looking middle-aged couples in glasses instead of girls in fashionable clothes and an efficient, if very arid (Teutonic, then?) feel to its contemporary art exhibitions. The Kunsthalle’s blockbuster show while I was there was called The Porn Identity - as the title suggests, an exploration of pornographic themes in society through relevant artworks as well as real porn films, climaxing in a five-by-four “rainbow wall” of televisions showing various snippets from famous porn films that changed according to their color schemes. The whole experience was remarkably sterile — I got more enjoyment out of watching three primly-looking students as they gazed in horror at Ron Jeremy being tied up and sodomized with a broom handle by a “liberated” French maid.

MUMOK next door has an impressive nine-story building but an equally dry demeanor to it. The permanent collection mainly consists of minor works by major Modernist artists that the museum can presumably afford, and despite owning the world’s best collection of Viennese Actionism, leaves them out entirely. The Nam Jun Paik exhibition there, likewise, mainly consisted of works MUMOK owned and was underwhelming as a result, while the retrospective of Austrian painter Maria Jassnig (a garish and dull version of Marlene Dumas, but with all the edge of Elizabeth Peyton) was hardly worth the two minutes I spent in it.

It's been said that the KHM, privatized a few years ago, has been attracted to contemporary art for the reason that it can afford to do exhibitions on a better scale than the institutions devoted to it across the street. This is a rather sad indictment, one that Russians will recognize only too well, but we should think relatively here. A Russian artist in a major world museum is a rare sight indeed, and rarer still is the opportunity to show alongside the great names from art history; indeed, an exhibition like this is practically impossible in Russia, with no museum to immortalize them on this scale and without the classical artworks to generate a proper dialogue.

The real significance of In Situ is not even the personal achievement for Makarevich and Elagina, timidly but visibly grinning from ear to ear while standing by their tower, but what should become a textbook example of how to show Russian art overseas. You’d probably have to be an alchemist yourself to put on an exhibition of Moscow Conceptualism in Europe somewhere that everyone understood for what it is, but context or no, it should be abundantly clear to anyone that Makarevich and Elagina are artists in the most classical sense of the word and entirely deserve their place amongst the old masters. Russia’s curators would do themselves a lot of good by going to Vienna and seeing how it could and should be done. In terms of artistic utopias, it doesn't get much better than this.

- 29.06Московская биеннале молодого искусства откроется 11 июля

- 28.06«Райские врата» Гиберти вновь откроются взору публики

- 27.06Гостем «Архстояния» будет Дзюнья Исигами

- 26.06Берлинской биеннале управляет ассамблея

- 25.06Объявлен шорт-лист Future Generation Art Prize

Самое читаемое

- 1. «Кармен» Дэвида Паунтни и Юрия Темирканова 3451696

- 2. Открылся фестиваль «2-in-1» 2342047

- 3. Норильск. Май 1268478

- 4. Самый влиятельный интеллектуал России 897659

- 5. Закоротило 822073

- 6. Не может прожить без ирисок 781983

- 7. Топ-5: фильмы для взрослых 758556

- 8. Коблы и малолетки 740812

- 9. Затворник. Но пятипалый 471084

- 10. Патрисия Томпсон: «Чтобы Маяковский не уехал к нам с мамой в Америку, Лиля подстроила ему встречу с Татьяной Яковлевой» 402961

- 11. «Рок-клуб твой неправильно живет» 370409

- 12. ЖП и крепостное право 345042