Комментариев: 2

Просмотров: 10599

Letter from Ekaterinburg: The "Dubaization" of the Urals

Here they believe in creativity and money just as firmly as they once did in socialism

Great ExpectationsThe place formerly known as Sverdlovsk is not just fascinating because it was once the industrial capital of the Soviet Union, but also because the city (about the size of Berlin) is undergoing a drastic redevelopment that is obvious the second you get out of the plane. The airport is new, with freshly laid marble and glinting aluminum siding. There are class-A business centers of glass and steel, and many foreign cars, some of them pretty fancy. There are migrant workers and megamalls, there is Metro and IKEA. The luxury highrises look like they could have been built the day before yesterday, albeit in Guangzhou. Maybe this is why the city was chosen to host the meeting of the Russian-Chinese Shanghai Cooperation Organization in May 2009, and the BRIC summit in June (BRIC is an economic club consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, which are projected by Goldman-Sachs to become the world’s leading economies by 2050, eclipsing the EU and the USA). Yekaterinburg, at least visually, has been perfected for the staging of such summits: you have both the legacy of Soviet-Fordist industrialism and the brave new world of Russian resource capitalism. Of course, you also can see the violence, the utopia, and the failure of both modes of production, which is, in my opinion, what could make Yekaterinburg into a really fascinating place for contemporary artists, whose presence and agenda is still far less obvious than that of big money and even bigger aspirations.

Although, if you listen to the curatorial rhetoric behind the Art Zavod festival - an exhibition of 36 artists and a dense three-day program of performances, workshops, lectures, and a roundtable organized by the Yekaterinburg branch of the NCCA - everything is pretty clear. As NCCA general director Mikhail Mindlin announced, ArtZavod is only a preview or a prototype for a far more ambitious biennial to be held in two years time at multiple venues throughout the region, not only in Yekaterinburg but other industrial cities of the region like Magnitogorsk, Nizhny Tagil, or Perm. Now this might sound like Manifesta (which as OPENSPACE.RU readers will remember was spread out over the region of South Tirol), but it lacks the “criticality” that projects like Manifesta always claim. As Yekaterinburg NCCA director Alisa Prudnikova affirms in her introduction to the project’s catalogue, “Новая капиталистическая реальность и индустриальные успехи край подкорректировали знаменитое утвреждение. "The new capitalist reality and the industrial successes of the region have corrected the famous slogan "The Urals are the locomotive of all-Russian power." By melting art into the life of defunct and operative Ural factories, we will visualize and rethink the region's specificity through its main symbolic capital."

You don’t need to plumb the depth of discourse analysis to feel the celebratory tone: the “new capitalist reality” does not prompt a critique, however fuzzy, or a subversive affirmation, however tricky, but announces a search for new sources of symbolic capital to be reinvested into regional rebranding. But in Russia, and especially, in the Urals, that is understandable somehow; contemporary art has to sell itself to global and local powers. It has to appeal not only to the Ford Foundation, which funded Art Zavod as its last project in Russia, but also to local business elites, for whom art has not yet taken on any representational or economic importance. Art, in other words, is still marginal to the Dubaization of Yekaterinburg.

Yeltsin’s factory

It took about forty minutes to get from the center of the city to the Art Zavod festival, held at the Бывшый Свердловский камволный комбинат, a sprawling complex in red brick whose construction was overseen by Boris Yeltsin in the late 1950s. Historical irony has it that the factory ultimately fell prey to shock privatization when Yeltsin became president; declining demand did not close the plant entirely, but in order to survive, it sublet to many smaller enterprises, including furniture manufactures and an industrial bakery. Part of the factory continues producing; some of the buildings still shake with the din of machines. That creates unusual conditions for contemporary art, which, at least in Western Europe, usually comes after production is almost completely gone. As everyone at Art Zavod was quick to point out, Yekaterinburg’s factories are still alive, at least for now, but their fate is undecided.

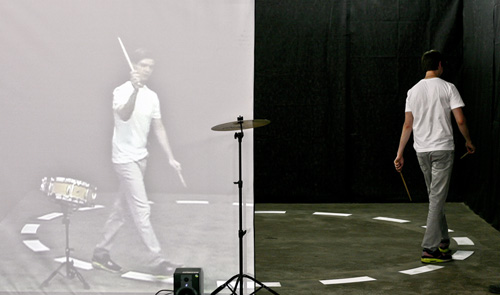

Many artists at the exhibition, curated by Xenia Fyodorova and Svetlana Usoltseva, seemed to anticipate total de-industrialization, treating the Kanvolny kombinat as generic abandoned industrial space, and replacing missing machinery (stanki) with new projective mechanisms of media art. There was a strong presence from the Kalingrad NCCA, with audio artist Danil Akimov occupying the factory’s disused thirty meter water tower with a very spectacular audio installation, in which contact microphones in the rusty floor boards transmitted the stamping and shouting of visitors up through the roof as a filtered signal. Media art was also the festival’s mode of communication with the West: Killian Kretschmer, a student of the ZKM in Karlsruhe, showed an interactive installation in which he walked in a marked circle to hit a cymbal, the other half obscured by a screen with a projection of him beating on a drum. The only world-star present was ZKM-director Peter Weibl, with an early film. The performance program included many light and sound shows, and that gave the festival a disco feel, except that no drinks were served, and work at the ailing factory continued around the corner, in a parallel reality.

To me, the more interesting projects at Art Zavod were those that tried to address this parallel reality in some way. One could find an embryonic form of a critical awareness for what class consciousness used to mean to industry and where it led in the installation of Victor Oborotistov (Ekaterinburg), who tried his hand at political symbolism for talking about trade union politics and the absence of workers. But the strongest appropriation of the half-living industrial space was the temporary dabloid workshop set up on the instructions by Leonid Tishkov, operated by a brigade of workers who had just been fired from the Factory. (See here for a complete description of the project). Tishkov’s absence made this piece and its inclusion of living labor very strong, putting in a long modernist tradition of deferred production. Another artist who interacted with the living factory and its waste was the hyperactive Ilya Trushevsky, who made a film of himself combining scraps of kanvol into a huge ball, which he then set on fire, covered with tar, and pushed up slopes like a latterday Sisyphos superstar, dressed in black as if to mourn the death of art. I don’t know what the film looks like, but I assume it is all about Trushevsky and his glamor-trash transformation into a one-man-factory surrounded by a grateful audience of teenage girls.

Drifting with the Interns

There were many teenage girls at Art Zavod, which brings me to the living labor behind the festival. Festivals like this are training grounds for cadres schooled in what a friend of mine calls the “dirty work of reproduction,” meaning not sexual reproduction, of course, but reproduction in its informational, medial, political, and economical senses. In the light of centuries of the gender division of labor (which a of this “dirty work” is done by girls. 30 of the 45 volunteers were girls in their early to mid twenties, outweighing 15 boys, most of whom were technical assistants. They gave the festival an aura of self-organization, with loose hierarchies and a more or less egalitarian tone. Watching them “work” (most of the time, they seemed to be talking to someone or waiting for something, rarely going into hysterics), I couldn’t help but wonder which part of their living labor was more important and profitable to the project as a whole: their organizational contributions, or their permanent presence as a potential captive audience. Had I been invited to the festival as an artist, and not as a journalist, I would have worked with them, because in my red eyes, they are the future proletariat of cultural production.

I am really grateful to all these volunteers, and especially to Agata Iordan, Darya Kostina, and Anna Bobrova, who took Elena Belova and Alisa Savitskaya from the Nizhny Novgorod NCCA and me on some great walks through the city, where we could somehow dream of what an Ural Biennale could be, which artists and/or curators we would invite to do research here, what texts and projects we could contribute, and so on. The place is perfect for a Situationist derive. The city’s streets draw straight Fordist lines that mimic the assembly line, but the architecture is highly uneven: constructivism (about 150 buildings total, some of them masterpieces), Stalinist empire, Khrushchevian five-story apartment houses, and some of the most spectacular social neo-modernism I have ever seen, which is currently being mutilated because everybody hates it. Each architectural period is connected to its own functions, violence and dreams, and taken in sequence, they tell a story of struggles and failures.

That story begins with the late post-constructivism of the Hotel Iset’ and the Village of Chechists, clearly a gated community for state enforcers, for whom the settlement’s anticipations of communism (erkers for everyone) are a privilege and not a general norm. And it ends, at least for now, with Yekaterinburg’s own version of Moscow City, a two-headed eagle glinting off the regional administration’s glass facade, and the bouncers in the night clubs who seem to think that they are working airport security. Somewhere in the middle of this story, on the outskirts of town, near the Uralmash factory and the UFO of Sverdlovsk’s famed constructivist “White Tower”, there is a ramshackle post-constructivist House of Culture, where one can find amazing marble applications on the brink between avant-garde abstraction and late avant-garde figuration. Up in the aktovy zal, there is an inscription, a central quote by Lenin, that reads: “Art belongs to the people.”

Criticizing the Creative Industries

Even if you think you know what that meant then, no one really knows what that means now, as one could see clearly at the roundtable that ended my stay in Yekaterinburg. This discussion merits an entire text of its own, and I was not the only one who was vexed: Kuba Szreder, a Polish curator and writer who has done extensive research on the relation between deindustrialization and contemporary art with a strong critical-activist note, was also there. Together, we gave the event the embedded criticality that projects like the Ural Biennial (and not just Manifesta) will need to gain any kind of international credibility. But after Szreder’s highly informative lecture of the ambivalent relation between contemporary art and neo-liberal transformation in places like Gdansk and Nova Hutta, the roundtable’s programmatic affirmation of the “new capitalist reality” seemed jarring.

This roundtable almost seemed like a mixture between a party meeting and a corporate training, where one could hear the most fantastic things: about how contemporary art could soon become Russia’s most important export after oil, gas, and precious metal (Mindlin), or about how important “creative industries” could be in reinvigorate the ailing industries of the Ural (Asya Fillipova, director of proekt_fabrika). Kuba Szreder and I tried to intervene by pointing out that financial data on both the art market and the creative industries are unreliable and inflated by marketing experts, and that the real backbone of a post-Fordist economy is the service industry, which, in turn, transforms art into a service rendered for a financial elite desperately in need for continual rebrandings.

Shouldn’t we talk about exploitation and privation, along with success and plenitude? Whatever happened to the class-consciousness of cultural producers and their sense of solidarity with all those parallel realities in which real industrial production is still taking place, and, for that matter, with all the less privileged branches of the service industry where it is painfully obvious that not everyone is an artist? Or, more broadly, whatever happened to the idea of art as a public service and as a venue for worker’s self-education? It seems difficult if not impossible to uphold or rethink such ideas in a place like Yekaterinburg, where the Russian brand of post-Fordism has taking hold with the same radicalism as Fordism did in the 1930s, albeit with much harsher means that in the West, molding people’s minds and depriving them of any critical and oppositional awareness. But in my opinion, it is precisely such an awareness is something the NCCA generally could and should try to foster, especially in a place like Yekaterinburg.

КомментарииВсего:2

Комментарии

-

Voila, merci.

-

You're very welcome.

- 29.06Московская биеннале молодого искусства откроется 11 июля

- 28.06«Райские врата» Гиберти вновь откроются взору публики

- 27.06Гостем «Архстояния» будет Дзюнья Исигами

- 26.06Берлинской биеннале управляет ассамблея

- 25.06Объявлен шорт-лист Future Generation Art Prize

Самое читаемое

- 1. «Кармен» Дэвида Паунтни и Юрия Темирканова 3451905

- 2. Открылся фестиваль «2-in-1» 2343475

- 3. Норильск. Май 1268940

- 4. Самый влиятельный интеллектуал России 897762

- 5. Закоротило 822250

- 6. Не может прожить без ирисок 782904

- 7. Топ-5: фильмы для взрослых 759849

- 8. Коблы и малолетки 741191

- 9. Затворник. Но пятипалый 471972

- 10. ЖП и крепостное право 408055

- 11. Патрисия Томпсон: «Чтобы Маяковский не уехал к нам с мамой в Америку, Лиля подстроила ему встречу с Татьяной Яковлевой» 403451

- 12. «Рок-клуб твой неправильно живет» 370760