The glittering facade of contemporary art covers the medieval lawlessness and monstrosity of power. But this isn't Moscow

If the rumors are true and Dubai is at the beginning of its end, the city-project of Dubai may later come across to us not so much modern as modernist. There’s something distinctly utopian about it, be that plans for a waterfront seven times the size of Manhattan, giant man-made islands designed to look their best from the air, the world’s tallest and most expensive hotel, the world’s tallest building, and even a rotating skyscraper worthy at last of Tatlin himself.For now, the utopia remains unrealized, and the status of several major ventures unknown. The skyline is imposing as it is superficial. Behind most of the supermodern 40-story-and-up business centers are rows of older, ramshackle, flat buildings that speak to Dubai's insignificant past; behind most of the windows there is simply nothing at all, with so many construction projects either not yet completed or still waiting for their occupants. 80% of Dubai's population is foreign, and tens of thousands of them have fled already, from laid-off Western professionals to members of the huge South Asian gastarbaiter class with no-one to serve.

But if the rats are fleeing the ship, the orchestra is still playing away, and they certainly make a good show of it. On the surface of it Art Dubai was a shining example of meticulous organization and a welcome upturn as if almost nothing had happened to the market, art or otherwise. This, the third edition of the fair, was its biggest manifestation yet, the centerpiece of the inaugural Contemparabia week featuring a biennial in the neighboring emirate of Sharjah, a Sotheby’s auction in Doha, a fringe art fair in Dubai, a book fair in Abu Dhabi and an enviable number of performances, educational programs, intellectual discussions, and networking opportunities on a level worthy of any cultural epicenter.

As a whole the fair straddled an odd border between being a working holiday for the Western art world and a powerful statement of Emirati intent to expand into it. The baying crowds on both sides, however, largely ignored this and treated the environment as their home turf. Cross-cultural meetings were apt to mean running into the exact same crowd as at any other fair anywhere else — and given the ready supply of alcohol and that the fair’s only official language was English, it was difficult not to feel at home.

Ditto for the locals, some of whom were apparently prone to behave as one assumes they would at a souk. Members of the royal family were known to wander the fair in large entourages, often wafting tidal waves of expensive perfume after them, accompanied by personal advisors and consultants who carried out inquiries on their behalf. For the most part these were not art experts, but rather the same consiglieri who advise their clients on the acquisitions of rugs, furniture, racehorses, yachts, and so on. Without the benefit of the tastemakers unversed Western collectors enjoy, this leaves aesthetic and financial decisions up to the buyer. Some were prone to ask for discounts of up to 80%, then attempt to place the items on reserve for the following five days.

Galleries at Art Dubai could also neatly be divided into two categories: those which had brought their stock in trade as to any other fair with an eye on the holidaying collector, and those which, with varying degrees of shamelessness, fielded an overt and in many cases astonishingly crude “Dubai selection”. The two Russian representatives neatly illustrated this. A participant since the fair’s inception, “Aidan” had gone for the same old same old, with works by Oksana Mas, Leonid Rotar, Filipp Dontsov, and Oleg DOU already familiar to the Muscovite.

Triumph, on the other hand, made its Middle Eastern debut with a selection of Russian artists either experimenting with, or suddenly receiving a newfound Middle Eastern flavor. And that came strongest from the least likely of sources, vigilantly glaring from the center of the stand — two close-ups of falcons in the unmistakable hand-print-and-gold style of Alexei Belyaev-Guintovt.

Thousands of miles out of context they looked not only harmless, but entirely appropriate — simple, striking, and almost domineering, with a clear nod to a hobby beloved of the local royalty and the glossy, shiny surface that transfixes the local collector like strings do overeager cats, if we judge by galleries in category number two. From a thematic point of view, for instance, the falcons called to mind Dubai’s currently stalled “Falconcity of Wonders” project. This consists of yet another enormous residential, business, and recreational complex, intended to resemble said bird of prey when viewed from outer space and to feature as its centerpiece a larger-than-life replica of the Eiffel Tower in hotel form. In short: typical Dubai.

But of those galleries Triumph was at once one of the least brazen in its ploy for the almighty dirham and one of the most effective as a stand outright — the works were all Russian and clearly so in context, all very much within the scope of what the gallery usually deals in, all appropriate to be shown alongside each other. Many Western galleries, on the other hand, were as blatant as you would expect. But the curious thing here was the almost total absence of production-line “blue-chip” pieces — there were a grand total of three Anselm Reyles, two Murakamis, and one Damien Hirst spot painting, which must be some kind of record.

Instead, this well-known affliction manifested itself through the glut of facile art from other Arab countries, seemingly repackaged and sold back to those who snoozed the first time round, and foreign art specifically pitched to fall within the strict parameters of local taste. Take for example PYO Gallery from Seoul. Fueled by a sale last year of Sung-Tae Park’s wire-metal horse sculptures to a member of the royal family, their stand this time devoted an entire wall to more works from the series and nearly all of the rest of it to other equine works (with one panda for good measure).

And there was a whole lot of shiny. You could find every conceivable snippet of Middle Eastern culture dressed in all that glitters — some shiny Kalashnikovs here, a biker jacket with Ahmedinejad’s face on it there, words and phrases from the Koran in everything from neon lights to book pages with fighter jets drawn on them. On this front the most prominent offender was Iranian Farhad Moshiri. For Dubai gallery The Third Line, he produced three canvases with glittery tropical birds sitting atop glittery tanks and weapons; Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin’s stand was dominated by his series “Golden Allah”, five frames with the name of the Muslim God in Arabic script rendered through glittery gold and glass beads.

Both of these were emblematic for much that was wrong with a lot of the art on show in general and an apparent shortcoming with the very idea of Middle Eastern contemporary in particular. At Perrotin, for instance, Moshiri had delivered the work very late and the stand had, as it were, been built around him at the last minute. Consequently it took on a distinctive gold hue — even the mighty Murakami was pushed to one side in favor of a big loop of golden balls by Jean-Michel Othoniel and a gold frame framing smaller and smaller gold frames within it by the oddly monikered French group Kolkhoz. Before long, the fair began to take on a bling aesthetic, robbing elements of a broad, rich and diverse culture of any possible meaning by glossing them over with the most vapid, egoistic motifs of Western materialism. Much as Belyaev’s work lost its capacity to frighten the viewer here, the ironic intent one would tend to expect from pieces like Moshiri’s was lost completely.

The best Arab works — or at least those by Arab-born artists — were serious and subtle. Nearly all the best regional artists here studied in the West, and for the most part still live there and work there today, which no doubt increases the risk of their being treated as “Arab Gothic” and calls a lot of their output, distinctly recognizable as Middle Eastern, into cultural question.

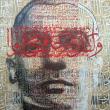

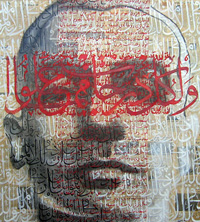

Two of my personal favorites directly engaged with this issue. Rising Iraqi-born artist Ayad Alkhadi split his childhood between Baghdad, the Emirates, and the UK, studied for his MFA at New York University, and left Iraq for good after the first Gulf War for Auckland. His “I am Baghdad” series (2008-9) mixing traditional Arab calligraphy with Western techniques of collage, here comprised from Arabic newspaper reports on the second Iraq War. These incorporated paint, charcoal, acrylic, and mixed media depictions of his own face, lending a questioning, troubling quality instantly recognizable as personal and profound. Exactly the sort of works you hope to find at a fair, in short.

Egypt-born, French-educated, and New York-based Ghada Amer’s subtle inversions of decorative aesthetics were welcome relief. “Le Salon Courbé” (2007) appears at first to be just a slightly eccentric designer living-room with chairs, wallpaper, and a rug in predictably bright “feminine” colors, but on closer inspection the embroidery revealed hints of blood spatters and hard-to-read dictionary definitions of “terror, terrorist, terrorism.”

Also intriguing was the 29-year-old Saudi Dr. Ahmed Mater — still a practicing GP in his small home village. He presented here a “Kabba” series (2008-9) in which the Islamic holy site was represented by a small black magnet, with metal filings circled around it, repelled by the other pole, in the guise of pilgrims. Egyptian Moataz Nasr had another good contemporary art take on Middle Eastern culture, with flower shapes made out of multicolored matches and an “Ice Cream Map” in jigsaw form of the Arab world — where conflict regions were left blank.

Notably, apart from Mater and Nasr, the most interesting Middle Eastern artists in the fair itself were those who had either studied in the West or at least owed a strong debt to it, as were the blander but prominently represented Lalla Essadi and Shirin Neshat as well as the already well-established Walid Raad. The nearby Art Park (disappointingly, an actual car park)’s lesser-known regional video art illustrated the problem further, largely consisting as it did of sloppy and banal “Arab Gothic”. Take among dozens Palestinian Larissa Sansour’s “A Space Exodus”, a student-level interpolation of Stanley Kubrick and the Apollo program which began with “Jerusalem, we have a problem” and was entirely predictable from then on. The one really notable exception was Khaled Hafez’s “Confessions of a Corrupted Mind”, a compelling hodgepodge of the same Egyptian “golden age” 1940s and 50s films Youssef Nabil idolizes with foreboding news footage of subsequent military coups, and that for its lack of refinement more than anything else.

What, on this evidence, Middle Eastern art really needs is a more developed local infrastructure to develop its approaches and distinguish them from Western ones. The Emirates themselves are an extreme case, and without a targeted attempt at this they will stay that way. The UAE not only has its first ever pavilion at Venice this year and will also be represented by Catherine David’s “Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage” (two qualities the country seems to lack by comparison with its neighbors) — but where is the art going to come from? The ninth Sharjah Biennial only had two answers — that is, only two artists from the UAE itself.

27-year-old Dubai native Lamya Gargash is often held up as the country’s bright hope and is taking prime position in the national pavilion. Her series “Presence” had an interesting conception — photographs of “abandoned or semi-abandoned” UAE living rooms, posed against the backdrop of the country’s rapid metamorphosis outdoors — but in execution was most reminiscent of a real estate or interior design catalogue. Reem al Ghaith, with the ink still fresh on her degree, fared better on the same theme with a rather Russian-style work, an expansive installation detailing the land left untouched in Dubai in between the towers and real estate complexes; but bar the theme it was difficult to distinguish from Western design.

Director Jack Petrossian envisioned the biennial as “untethered by themes and curatorial agendas”, and that was largely what happened: under the vague banner of “Provisions for the Future”, the exhibition became more about the fact of having a biennial than any concepts explorable through a biennial. Though most of the works were commissioned directly for Sharjah, artists largely stuck to their usual oeuvre. Unsurprisingly, the exhibition proved diverse and lively, but incoherent and in need of a bit of pruning. Highlights were predominantly Western, including New York-based Argentine Liliana Porter’s metaphysical ruminations on man’s place in the universe through the lives of miniature toy figures, a disorientating maze with clips of barking dogs (inspired by Auschwitz somehow) by Pole Agnes Janich, and two videos from Slovenian duo Nika Oblak and Primoz Novak. In the first, the artists appeared trapped in a small television, attempting to force a way out by kicking and punching at the sides of the screen, at which the orange fabric surrounding the box moved accordingly; the second was a tongue-in-cheek film fictionally documenting their journey to Sharjah by land with a wheelbarrow.

The biggest disappointments were the site-specific works, which, like the exhibition itself, seemed primarily to be about their own and the biennial’s existence. Maider Lopez’s contribution consisted of placing a public fountain and painting a makeshift football pitch in the square outside the museum. Inside a large silvery ball made by the German Karin Sander rolled down the slope along which most of the exhibitions were set, reaching a rather pointless end at the bottom before being brought back up by a security guard.

Overall, as slickly organized as the events were, it’s hard to see how they can contribute to the development of regional art when the focus is so heavily weighted towards Western influences or the buyer of “Arab Gothic.” The problem reaches a sort of absurd point in the Emirates, with Abu Dhabi’s planned Louvre and Guggenheim branches taking a prime position over support for domestically produced art. Dubai and Sharjah are in a far more precarious position both financially and artistically, given their heavy reliance on foreign investment to keep the cranes moving and foreign culture to keep galleries in business — especially since the cost of living and lack of state funding make the struggles of being an artist in Moscow look tame.

And regardless of any good regional art the events turn up — not an entirely insignificant amount — one wonders what ultimate function contemporary art serve in their rulers’ grand plans. Signs they are slowly expanding their ultra-conservative tastes are not promising: apparently the Sheikha of Dubai bought one of the worst works at the entire fair, a thoroughly repulsive painted Buick by Chinese artist Ma Jun. It’s likewise difficult to envision what kind of real hub for contemporary culture either emirate can function as when their laws are so medieval, including one in Sharjah barring unmarried women from accompanying men in public places and one in Dubai promising jail time for natives pregnant outside of wedlock. I left with the feeling that contemporary art here is just another Western horse in the palace stable, a simultaneous attempt to make the Emirates appear a modern cultural hub and a part of a vibrant, emerging region, when they are nothing of either sort. And if the money dries up, most likely the art will go with it — back to where it came from, and back to where it belongs.

- 29.06Московская биеннале молодого искусства откроется 11 июля

- 28.06«Райские врата» Гиберти вновь откроются взору публики

- 27.06Гостем «Архстояния» будет Дзюнья Исигами

- 26.06Берлинской биеннале управляет ассамблея

- 25.06Объявлен шорт-лист Future Generation Art Prize

Самое читаемое

- 1. «Кармен» Дэвида Паунтни и Юрия Темирканова 3451865

- 2. Открылся фестиваль «2-in-1» 2343452

- 3. Норильск. Май 1268840

- 4. Самый влиятельный интеллектуал России 897731

- 5. Закоротило 822203

- 6. Не может прожить без ирисок 782782

- 7. Топ-5: фильмы для взрослых 759656

- 8. Коблы и малолетки 741081

- 9. Затворник. Но пятипалый 471727

- 10. ЖП и крепостное право 407992

- 11. Патрисия Томпсон: «Чтобы Маяковский не уехал к нам с мамой в Америку, Лиля подстроила ему встречу с Татьяной Яковлевой» 403320

- 12. «Рок-клуб твой неправильно живет» 370703